It’s taken me longer than usual to craft this blogpost. In truth, I wasn’t sure where to begin. Learning about the African Savannah Bee — Apis mellifera scutellata — carried my imagination into medieval royal courts, to considering the feminine principle, to the San Bushmen and their primitive depiction of bees and their hive in a painting on a rock face on Zombeparta, a huge bald kopje on my uncle’s farm in northern Zimbabwe.

Learning about beekeeping in southern Africa showed me it was a pastime that required Chuck Norris-type nerves and a jolly good bee suit. Elephants are known to panic when they hear the buzzing of African bees around a hive; it took everything in me not to do the same when we were warned about their sting-to-kill policy if you really piss them off. Which, as it turns out, isn’t hard. Bees are wild animals; African Savannah Bees are wild, aggressive animals. They don’t like the smell of fear; they don’t like sudden movements, vibrations, or loud noises; they don’t like expensive perfumes or the smell of sweat or freshly cut grass. Bees also don’t like the color black, which is why a bee suit and veil are usually white. All of these things can turn a docile colony into a marauding army, killing pets, chickens, livestock and us, if we happen to be in the wrong place at the wrong time.

When hearing this I thought to myself, “Okay, Annabel, does this mean if you’re going to keep bees to pollinate your garden and harvest your own honey, you’re going to have to tone down your hygiene standards, buy a new (light) wardrobe, practice talking softly and walking stealthily, and live in uncut grass without any dogs, cats, or chickens?” That our house is open to the elements, without a door in sight, didn’t increase my confidence.

So much for me communing with colonies of African bees in a way the San Bushmen have done for thousands of years, with nothing on but animal hide to cover their dangly bits. I bought a pair of cherry red overalls, which bees in their color spectrum see as pink, so won’t attack; a white bee jacket and veil; a pair of thick black Bata gumboots, which they will attack; and a pair of white leather gloves with cotton arms that extend up beyond my elbow. You’d think I’d be impenetrable. Wrong. Bees often find a way in, and when under attack you’d think your first option would be to run like hell, hoping that wherever you end up would be sting-proof. Wrong. As more and more angry bees gather around the hole in which the first attacker entered, you have to stay calm while slowly retreating from the hive. Then you run like hell.

Hearing this reminded me of my first (and only) attempt at scuba diving off the coast of Australia, where I was told that if I saw a shark I should never shoot straight to the surface because it would induce the Bends and I’d die. The thought of not being able to hightail it, screaming my lungs out, after being stung by bees inside my suit, induced in me a panic which, combined with boiling hot “beeware” on a boiling hot day, led to an instant attack of claustrophobia. (This was just after we’d been told that our instructor was going to demonstrate opening a hive at a time when the bees were at their most aggressive, so to be careful. In March, when the rains are coming to an end, the hive is filled with older bees about to die and they defend the hive fiercely.)

Not once did my anxiety about beekeeping eclipse my genuine wonder in the bees themselves. Their purity of motive, their sophisticated methods of interactive communication, their application of industry and intelligence, and their harmonious coexistence. Their female sensibilities!

Community organizing in a beehive is unparalleled. No one argues and the job gets done. Every bee has its place: there are guards, scouts, nannies, nurses, groomers, builders, ventilators, foragers, water gatherers, cooks, cleaners, and meteorologists. All are there to protect and nurture the queen, who in turn ensures the health and well-being of her household. The queen moves slowly, majestically, leaving pheromone-laced paw prints in her path. She is surrounded and cleaned by feeder bees as she moves. They all face her. She talks as she walks, sending messages of reassurance to her 60,000-strong colony and spends each day renewing and building “the spirit of the organism.”

I bet you never knew that bees are fully-fledged members of the Mile High Club — yes, they have sex while they fly — or that they dance like J-Lo? It’s their way of communicating what sort of food is available to forage beyond the hive. If a bee is really giving its booty a good shake, it means there’s top quality nectar and pollen outside. The round dance is used to recruit workers to work on collecting nearby, while the wagtail dance signifies there is food further afield. On the course I saw an enthusiastic wagtail dance, illustrating to me just how synchronized they are with one another and their environment. It’s no wonder bees have inspired storytellers, were revered by the Ancients, and are still linked with magic, love and prosperity.

The beekeeping course was organized by our friend Theresia van Zyl, who’s been working with Dutch beekeeper, Frank Leenen, for the past three years. Theresia grows seeds and makes essential oils on her partner’s family farm in Mazabuka, five hours north of Livingstone. With so many flowers being grown, beekeeping was a no-brainer: bees are super-pollinators, and effective pollination positively impacts the quality of the produce.

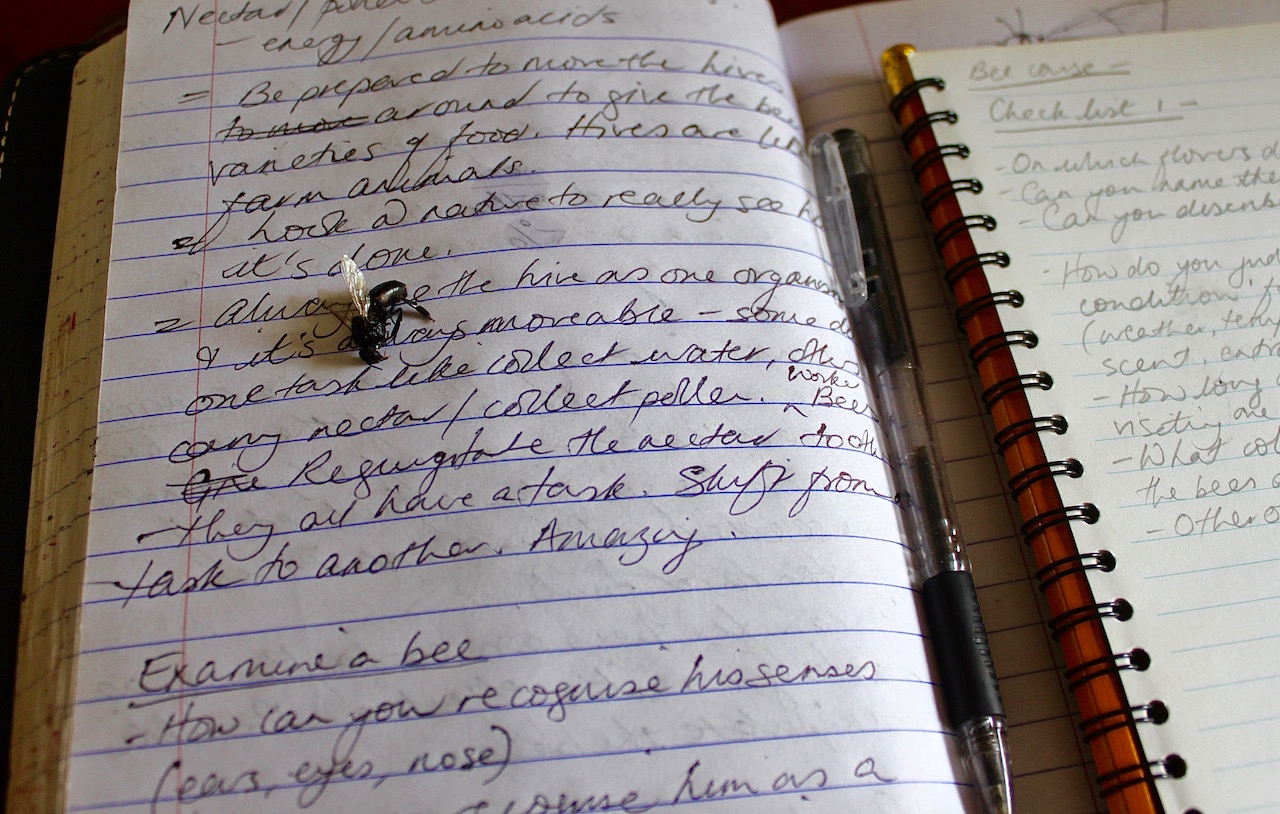

Frank taught us about basic beekeeping, which involved classroom theory as well as field work. He talked us through how bees built a hive, and showed us how to approach it in the field. He taught us to regard the bee colony as one organism, not just a single bee. We learned about brood nests and supers, propolis and wax, as well as the basics in beehive management. Frank showed us how to use the beekeeping tools, how to extract honey from the comb, and how to melt down the wax. He taught us about safety and the importance of the smoker, a tool that must be used as a warning aid not a weapon. Frank gave us ideas of what to do if we’re attacked (an assistant should carry water to wet you; have a room or your car ready to dive into; move through dense bush to sweep off the bees).

The first thing I did after returning home from the course was to ask Chris if he’d help me until I felt more confident. “I knew it!” he said, laughing. “I knew you’d rope me into it.” Chris, you see, is the second son of Hanni Aston, who in her day was one of Zimbabwe’s better known beekeepers. Such was her comfort and connection with her bees, Chris told me that in the years before her death, Hanni could open a hive without wearing a veil, let alone a suit. The same could not be said for Chris. He was stung so often assisting his mother, I detected a definite allergic reaction to the thought of helping me.

My biggest challenge as I start to work with bees is learning to feel comfortable around them. To not be afraid. A theme that ran through our three-day course was that when you learn the “language” of bees — when you have empathy, insight and respect — it transforms those initial tentative explorations into a satisfying, absorbing and productive pastime. In the months ahead I’ll be documenting my experiences as a beekeeper here on the blog, as long as the bees don’t completely undo me at the outset.

20 Comments

I salute your bravery my friend! Good luck … 🙂

Haha! Thank you, Georgie. Hold that comment, please, at least until I present my first jar of honey. There’s so much that can happen between now and then!

I loved this ! Such education and entertainment – bedtime reading… Check. Any future in beekeeping … Nup. But very much look forward to your bee keeping adventures. Brave Annabel keep us informed ???

Thank you for your kind comment, Mo. I look forward to documenting my adventures with bees, even if I am a little nips about it all! 🙂

Your insatiable curiosity for knowledge and new experiences is taking you into dangerous waters now 🙂 Keep safe….I’ll be following this blog to be better informed as to how to avoid what for me is a ‘life threatening’ attack. My Epipen will be very close to hand on our next visit! Well done!

Thank you, Bridgey. You can be sure the hives won’t be near the house; they’ll be in the bush beyond, but close enough for the bees to collect the pollen and the nectar from all our flowers. I might just ask you to bring a few extra Epipens, ahem … I need one now, in fact, to undo Chris’s allergic reaction to helping me!

😀 😀

[…] via The Not-So-Secret Aggression of African Bees – An Introductory Course to Apiculture — SavannaBe… […]

Step by step, sting by sting until the walk becomes a waltz and you’re in tune with the wonderland of the bee kingdom … United … Fearless … Stingless

You should keep writing, Mo. Seriously. So much gratitude … xo

Oh, bravo! Steve tried bees twice and neither worked out well. The first flew away, the second died. Alas. My great grandmother was much like Chris’ mom. Maybe I should try. 😉

Thanks, Michelle. Oh, please do! Then we can compare notes as we go along! 🙂

Good luck Annabel! I hope it doesn’t take too long until you are as one with the bees! They really are fascinating creatures.

Thank you, Cynthia! I hope it doesn’t take too long, either! You’ll be relieved to hear that we’ll be just starting out when you land on our terra firma in June. (Not sure how safe it will be after that, haha!) 😉

Oh Annabel – this must be the most fascinating post of the year from anyone, and the most informative – and, for silly-billy me, the most frightening! I so carefully back off even from our very ordinary garden bees especially interested in our native flora . . . Having woken up way back in summerish Norway to find a bee had decided to snooze in between my legs and showed her anger when I dared move, I now triple-check everything in the summer months! I DO leave them to it . . . Happy Easter and thank you for a post I’ll read again!!

Oh my goodness! Who could blame you for triple-checking thereafter? Poor you! I’m moving forward with this new pastime filled with excitement tinged with trepidation, so we’ll see how it pans out. Much gratitude, as always, for your interest and support.

I kept bees for 5 years until I decided it was just easier and more sensible to buy my honey. Now 30 years later I have 5 hives on my property but, with someone else to manage them, I get 10% of the honey and 0% of the pain. Still it’s great to try out and I wish you good luck!

Thank you, Mike. It sounds like you made a wise move. I’ve always wanted to keep bees, therefore I’m looking forward to giving it my best shot. Whether or not I misfire remains to be seen!

Well done. This is so necessary to keep us all alive. We need bees and people like you to keep the bees going.

Thank you so much for your sweet comment, Sally. We do need bees … and I so wish more people understood this. All the best to you, Annabel

Comments are closed.